Resources

🙏 This article would not have been possible without the inspirational dialogues with my dear friend and ex-colleague, Andris Fajtai, who provided expert insights on the topic as well.

Thank you dear Andris!

Introduction

What is music? Is it a piece of art or a tool? A tool for what purpose? And what could Mozart and digital cameras have in common? Perhaps not much, or maybe more than you might think. Let’s find out!

Art or a Tool?

What is functional music? According to the definition:

“Functional music is that music which, when properly administered, accomplishes specific predetermined ends other than entertainment or pleasure.”

R. L. Cardinell and G. C. Henry, Guide to Industrial Sound (1944)

The key phrase here is “other than entertainment or pleasure.”

Consider photography. Is it an art or a tool? When you think about Annie Leibovitz’s work, you might quickly say that photography is a form of art. However, consider aerial photography, passport photos, or crime scene investigation photos; it’s hard to argue that these are art. Photography can be both a tool and an art form simultaneously.

Can we say the same about music? Definitely. In fact, music without any functional purpose is a ‘relatively’ new concept in human history.

Historically, music and song were used to:

- 🔔 Signal events: such as the beginning of a hunt or to warn of danger.

- 📖 Pass down stories, traditions or history - long before writing was invented.

- 🙏 Rituals and ceremonies: for various cultural practices.

And we still use music for practical purposes today:

- 🎏 National anthems: to express national identity,

- 🎒 Educational songs: to help children learn the alphabet, numbers, and other basic concepts.

I think you get the idea.

OK, But What About Mozart?

After discussing photography (I’m not done with that, stay with me), let’s talk about Mozart’s music and an interesting theory called the Mozart Effect. Although the original study by Rauscher, Shaw, and Ky1 did not use the term “Mozart Effect,” it became popular to describe their findings.

They observed that after listening to Mozart’s music, participants showed a temporary improvement in spatial-temporal reasoning skills.

🙅 However, the media exaggerated these findings, leading to the widespread but incorrect belief that listening to Mozart makes you smarter.

More research has confirmed that listening to music - not just Mozart’s - can positively affect your ability to manipulate shapes in your mind, although this effect is temporary.

It’s not the genre or artist that matters most; what is more important is whether you enjoy the music you’re listening to.2

Alright, let’s move away from science and research for a moment. While music might not boost my intelligence, can it help me concentrate? Absolutely, and I believe many would agree. For people who do creative work - I dare to include myself here, as a developer - music can be a powerful tool to help them focus and stay in the flow.

This is exactly what Canon, the camera company, had in mind when they released their very first music album.

Wait, what?

Canon Made a Music Album

Yes, you read that right. From the press release:

London, UK, 15 January 2024 – Canon unveils its first ever album, AutoFocus, crafted in collaboration with the British Academy of Sound Therapy and available on Spotify from today.

The first question that comes to mind is, “Why?” The one-word answer: marketing.

Canon made it clear in the first paragraph of their press release that the album was “specifically designed” to be played on their latest innovation—a Bluetooth-enabled speaker with a lamp. (You can find it on the net with a quick search, I won’t link it here)

I’m afraid I won’t be buying this lamp, but I found the album quite interesting. It was produced by Lyz Cooper, the founder of the British Academy of Sound Therapy, and Jimmy Day of LOYAL. Surprisingly, I discovered that I already have several LOYAL tracks in my commute playlist - another good point.

Although I have no experience with sound therapy and can’t comment on the album from that perspective, the fact that it was carefully designed as a perfect soundtrack for creativity, backed by research and studies from BAST, convinced me to give it a try.

From Random Playlists to Engineered Music

We already have the perfect soundtrack for concentration - it’s called Lo-fi. Lo-fi, or low-fidelity music helps listeners focus on their tasks by minimizing complexity and distractions. With its lack of complex lyrics, and operates with simple and repetitive melodies, or ambient sounds, Lo-fi is an ideal choice for creative work or studying.

I usually go with a Lo-fi playlist in Spotify for my daily work, but I always have the feeling that these playlists are imperfect. I don’t blame Spotify or their algorithms; as I discovered, the issue isn’t that I get bored of the songs. Instead, it’s the disruption caused by the appearance of a perfectly out-of-place song.

What if I could use a soundtrack designed by a sound therapist specifically to help me get into and stay in the flow? Is it possible to engineer an album for a given purpose? It seems like it is.

💡 If you interested in the methodology behind the album, I encourage you to read the blog post from BAST as I am focusing only on some key points here.

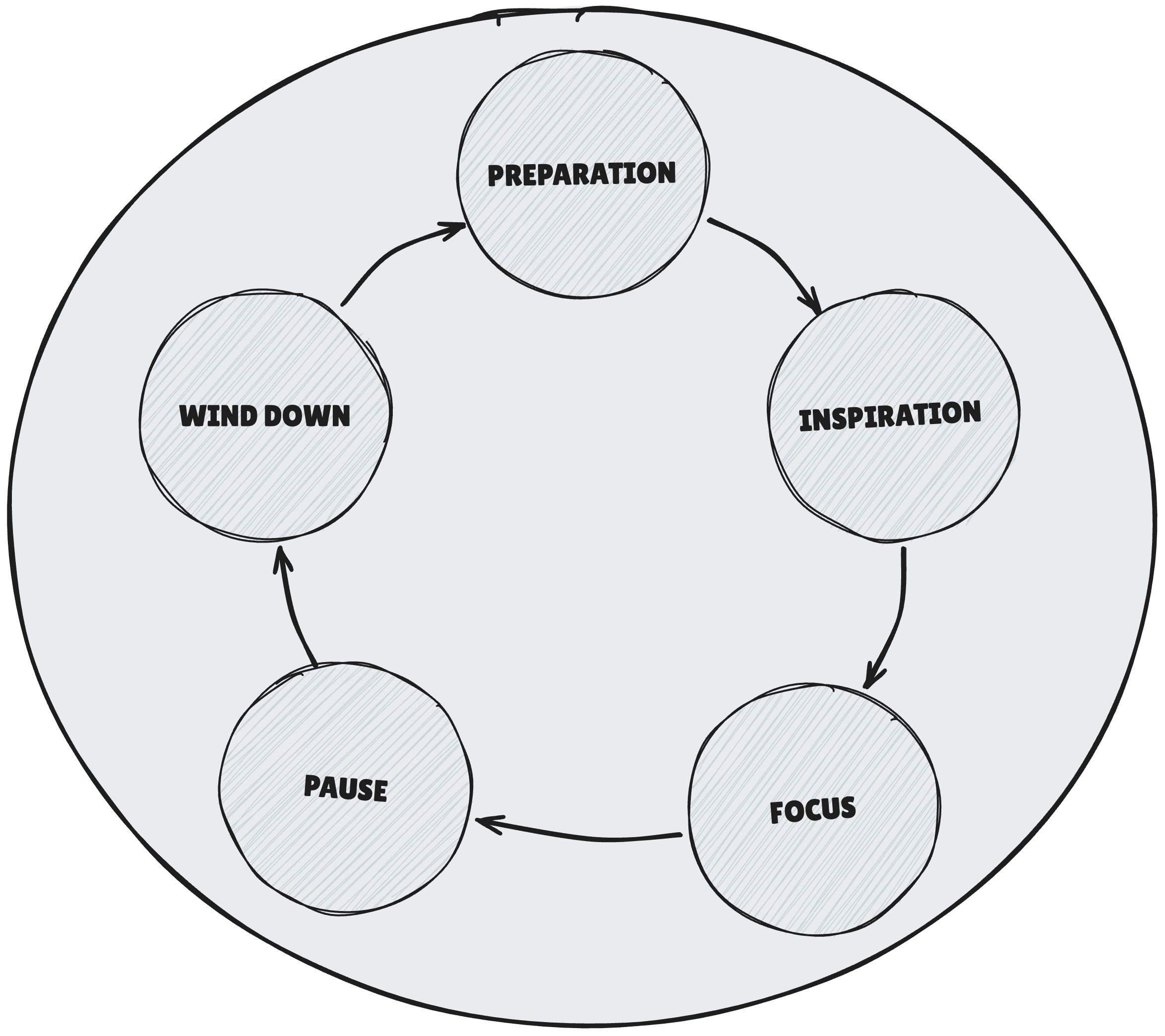

The album itself consists of 7 tracks, each carefully composed to enhance the listener’s focus. To fully benefit from the album, it is crucial to listen to the tracks in order rather than shuffling them. Unlike traditional Lo-fi music, which typically maintains a consistent and low BPM, this album experiments with varying tempos and rhythms, as well as different high and low frequencies. Based on study results, the album guides the listener into a more alert and concentrated state with its rhythmic tracks, then transitions to lower and longer frequencies to prevent brain fatigue and release tension.

A key track, called ‘Pause’, plays a significant role in the album. As the longest track at exactly 8 minutes, it is designed to give the listener a chance to relax between two productive sessions. This effectively doubles the album as an ‘audio pomodoro timer’, which I liked so much.

One more thing I found interesting is that the album plays so boldly with vocals. While most Lo-fi tracks are instrumental, AutoFocus includes vocals - especially in the last two tracks. Surprisingly, the vocals are far from distracting; I found them somehow rewarding as they helped me to ramp up my attention after the ‘Pause’ track.

Engineering Music for Purpose

I believe that the AutoFocus album is a splendid example of how music can be carefully planned or - dare I say, engineered - to serve a specific purpose. The concept isn’t groundbreaking; I am alone could name a few examples of similar endeavours: Headspace and other popular meditation / mindfulness apps provide professionally crafted music and soundscape streams with the same goal in mind.

The Advent of Generative Music(?!)

I urge not to confuse albums like AutoFocus with AI generated music. While there is a plethora of AI-generated music available, I am confident that, at least for now, we cannot expect the same level of effectiveness solely from AI-generated music without the human touch of a sound therapist or composer. To illustrate that, I encourage you to watch this very entertaining video from Answer in Progress:

Creating music for a specific purpose, like helping you focus, requires significant effort. However, this could change as we enter the era of Generative AI. I envision a future where AI assists composers and sound professionals, much like Copilot helps developers write code. Importantly, humans will remain in control.

In the future, I believe AI will offer tailored music experiences based on our mood, current condition, and the type of task at hand. It might even adjust the music in real-time based on feedback from the listener or the environment. This isn’t far-fetched, we already wear a bunch of sensors on our wrists and elsewhere.

Finally, my ultimate question: do we even need such a tailored music experience? Should we view music or other forms of art as tools? Personally, I’m unsure. For now, I’ve been listening to the AutoFocus album while working for the past 5-7 days. I feel more focused and productive, and surprisingly, I haven’t gotten bored of the album yet. Is this due to the music itself, or because I want to believe in its effectiveness? Honestly, I don’t know — perhaps it’s a placebo effect. Time will tell.

Conclusion & Takeaways

In conclusion, while an album from Canon or any professionally crafted music may not directly make truck drivers, doctors, and developers better at their jobs, or make our kids smarter, it can significantly enhance our working experience. Music has the power to reduce stress and improve focus.

Just a gentle reminder amidst the AI hype: humans use tools, have feelings, and can get tired or stressed. Ultimately, music — regardless of the genre — is a remarkable piece of art. So, be a human, and don’t hesitate to use it as a tool whenever you’re in the mood for it.

Rauscher, F. H., Shaw, G. L., & Ky, K. N. (1993). Music and spatial task performance. Nature, 365, 611. https://doi.org/10.1038/365611a0 ↩︎

Nantais, K. M., & Schellenberg, E. G. (1999). The Mozart Effect: An Artifact of Preference. Psychological Science, 10(4), 370-373. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00170 ↩︎